PPE and the problem of diarrhoea in finishing pigs

by Henning Bossow

Veterinary Practitioner

D 27318 Hoya - Germany

Gastro-intestinal problems have always been the cause of considerable losses in pig production. Originally they were detected only if obvious symptoms were apparent in the form of an altered manure consistency. We have since learned that even weaknesses in performance could be a sign of pathogenic changes involving the pig's digestive tract. Another lesson from practical experience has been that several possible explanations should be considered when grow-finish pigs are affected by diarrhoea.

1) PIA: Commonly, about 10% of the finishing pigs clearly leg behind the rest of the group in terms of their weight and have a pale skin. (Photo by Bossow)

2) PHE: Signs of blood-flecked manure are evident beneath the tail. (Photo by Bossow)

3) PHE: Manure occasionally contains pure blood. (Photo by Bossow)

4) PIA: Shown next to a section of healthy gut for comparison is the convoluted and theckened mucous membrane of a diseased pig. (Photo courtesy Elanco Animal Health)

For a long time the practitioner's diagnosis of bacterial enteric diseases was generally limited to just 2 possibilities which were differentiated entirely according to the age of the animal. In young pigs the aetiological agent was assumed to be E. coli whereas Serpulina hyodysenteriae was the suspect at the growing and finishing stages. The appearance of blood flecks in the manure of a meat pig was seen as near proof of swine dysentery due to Serpulina spirochaetes. Successful treatment using Imidazole preparations seemed to confirm this and led to the mistaken belief that all non-dietary and non-viral scouring in the finishing house could be attributed to the same agent.

The growing unreliability of the therapies was postulated to indicate an increasing resistance of the pathogen to the medication applied.

It was only in the 1990's, above all through the introduction of the polymerase chain re action (PCR) diagnostic method, that other pathogenic bacteria became identified as regularly causing enteric diseases. Now we had proof that a condition such as spirochaetosis could depress productivity without producing more overt clinical signs and that blood-flecked diarrhoea could appear in the absence of Serpulina hyodysenteriae: it might be due, for example, to the ileitis organism today called Lawsonia intracellularis.

Unfortunately, the situation facing the pig practitioner has not become any easier despite the help of modern diagnostic methods. The tendency to suspect one agent in every case simply seems to have swung in the other direction. A few years ago each instance of diarrhoea containing traces of blood was equated with dysentery, these days the first nervous question asked by producers after the discovery of blood in scours from their finishing pigs has become: is it PPE?

This shift in focus towards the porcine proliferative enteropathies or PPE may be well-deserved. The term is used for an assortment of disease images in the growing and finishing pig, all associated with a Lawsonia intracellularis infection. Details remain incomplete so far about the distribution of the Lawsonia agent in pig populations, with little agreement between different authors in different countries, but an infection rate of up to 80% has been cited after some spot checks of herds in individual areas. In our practice in Lower Saxony, Germany, we can identify the agent in approximately 25% of the pig units for which gastro-intestinal diseases are a perpetual problem. It has a causal effect on more than twice as many enterprises as are affected by Serpulina hyodysenteriae.

| Figure 2: Overview of PPE´s clinical forms | |||

| PPE type | Subclinical PPE | Cronic PPE (PIA, RI, NE) |

Acute PPE (PHE) |

| Age range most affected | 3-30 days* 2-12 months* |

2-5 monthts | 4-12 months |

| Manure | normal | normal-pastey brown-watery |

normal to bloody/watery |

| Animal behavior |

unchanged | unchanged | weak, lost appetite |

| Skin colour |

unchanged | sometimes pale |

some dead pigs extremely pale |

| Runts | none | about 10% | none |

| Deaths | none | seldom | peracute deaths: up to 5% |

| Risks | unknow factor can trigger other forms |

severely depressed group performance |

sow-to-piglet transfer infects the population |

Without a doubt, one of the important differentiations in diagnosis must be between PPE and classic swine dysentery – especially since the Serpulina have been found in PPE-affected groups.

Their clinical signs show many similarities although an initial distinction can be made in more than a few cases through the exact observation of samples of abnormal faeces. Blood-flecked manure that contains fibrinal strands without obvious mucous is a clear sign of an infection with the Lawsonia. Also, the sunken flanks of an animal in otherwise good condition which occur with an acute Serpulina hyodysenteriae infection are not typical of the type of PPE known as proliferative haemorrhagic enteropathy or PIA, while pigs chronically diseased with the alternative type called porcine intestinal adenomatosis or PIA are recognisable as runts.

In the case of blood-flecked diarrhoea, differential diagnosis can rule out Salmonella, coliforms and clostridia as possible causes. Even so, the symptoms might be linked to gastric ulcers. Stunted growth (without or without altered manure consistency) could signify a spirochaete infection or the presence of parasites.

Blood sample analysis for IgG antibodies, especially from chronically infected animals, offers one possibility to begin the diagnostic process after the first clinical suspicions are aroused. Faecal material is easier to sample, but we need to remember that the intracellular Lawsonia agent is detectable in faeces by means of PCR only in fewer than half of acutely infected animals. So one must reckon with a high probability of false negative results. Both acutely and chronically infected pigs should be included in a pathological/anatomical examination and this may be followed by a PCR check on altered bowel segments taken from the jejunum/ileum.

Of the 4 different disease images that can be summarised under the heading PPE, the form referred to as PIA involves changes in the distal jejunum and in the ileum whereas regional ileitis is limited to the ileum alone. Neither results in much more than poor growth. However, heavy bleeding in both bowel sections can occur suddenly with the third variant, PHE, and can lead to the animal's death. Before then, the acutely infected pig is weak and loses its appetite; its excrement appears to be mixed with an extreme amount of blood which trickles from the anus down the backs of the legs. The fourth type is a necrotic enteritis that produces a severe and permanent reduction in the resorption area of the gut, resulting in obvious runts although causing fewer deaths.

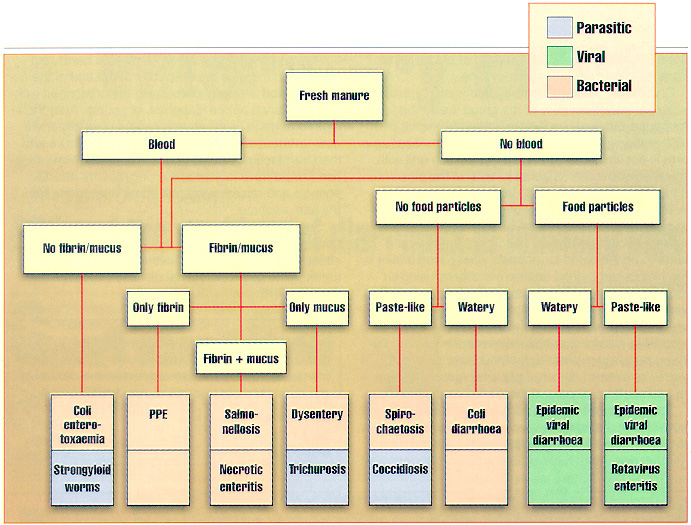

FIGURE 1: Differentiation process for Assessing manure samples

Usually Lawsonia enters a pig by the oral route after an intake of contaminated manure. In the case of a new infection the agent may be detected in the animal's own faeces 7-14 days later and the first anatomical or pathological changes appear after 12-14 days. Clinical symptoms take longer than this to become noticeable, however, so shedding starts and is able to spread the infection before the onset of the disease becomes suspected. At present it cannot be said whether pigs are free of the organism following a primary infection, but an immunity lasting about 12 months seems possible in those that survive.

Subclinical PPE can occur in suckling piglets from a Lawsonia-free sow even in their first month of life. It is also an occurrence in piglets from the second month onwards, where they have acquired a colostral immunity. The animals appear to have no symptoms, yet can suddenly develop clinical signs through the intervention of a still-unknown trigger mechanism or perhaps of other infections. Clinically recognisable chronic PPE shows itself as the PIA, ileitis or necrotic enteritis diseases, usually between the ages of 2-5months and in finishing pigs. Their manure is normal to paste-like in consistency with flecks of blood and is brown in colour or watery. The pigs – often comprising 5-10% of the total group – show few outward signs except that they fall noticeably behind in growth. Deaths are rare.

A mortality rate of up to 5% of the group is possible with the acute form of PPE, by contrast. This strikes particularly at herds which have a high level of hygiene and at breeding gilts. It seems to be triggered by a stress such as the move to new housing. Affected pigs may be found dead without having shown signs of being ill. In other cases an illness lasting from an hour to a few days can develop in which the condition of the animals is poor and their manure is either blood-flecked or contains a quantity of blood. Sometimes, too, their skin is extremely pale.

Chronically diseased individual animals seldom make up more than 50% of the group inside the finishing house. Generally in well-managed herds we find 10% of the pigs are affected. The acute haemorrhagic form is not limited to gilts. On a grow-finish unit with good hygiene it can strike up to 15% of the pigs and, in the process, lead to 2-3% losses.

Treatment recommendations can only be postulated from practical experience until detailed antibiograms become available. Injection therapy would seem to be indicated for animals whose feed intake is low. I have had a good degree of success using lincomycin/spectinomycin or tiamulin solutions. Injecting tylosin also can reduce symptoms. A long-lasting antibiotic treatment through the feed and/or water is needed to restrict economic losses in an infected finishing population. While symptoms disappear during a course of tiamulin, for example, they quite often flare up again within 10 days of the end of medication.

To prevent an outbreak of the disease I would say that tiamulin, lincomycin/spectinomycin, tetracycline and tylosin are all equally effective. A prolonged 100ppm dosage of a tylosin preparation also removes the symptoms in many cases of infected herds, but medication must be maintained until the end of the finishing period – always observing the prescribed withdrawal interval before slaughter, of course. After those pigs have gone I recommend careful cleaning of the compartment to clear away any trace of manure and then disinfection. Additionally, the diagnostic investigation should have looked at the origin of the affected animals and raised questions about restocking from the same source.

One other point that should be made relates to housing and management . Ensuring these are as stress-free as possible minimises the risk of an outbreak of the gastro-intestinal diseases known collectively as PPE.

aus -Pig International - May 1999 - Volume 29, Number 5-20A-